- The group is gaining territory and driving Afghan civilians abroad. But its long-term prospects remain dim

The Economist

WHEN the Taliban announced the start of their annual spring offensive last week, Afghans braced for bloodshed. This week, it came. On April 19th, during morning rush hour, a member of the Taliban drove a truck laden with explosives to the gates of an elite military base in downtown Kabul and set off his charge. Amid the dust raised, gunmen stormed the compound; a lengthy battle with security forces ensued. At least 64 people were killed and about 350 wounded in the deadliest strike in the capital since 2001.

WHEN the Taliban announced the start of their annual spring offensive last week, Afghans braced for bloodshed. This week, it came. On April 19th, during morning rush hour, a member of the Taliban drove a truck laden with explosives to the gates of an elite military base in downtown Kabul and set off his charge. Amid the dust raised, gunmen stormed the compound; a lengthy battle with security forces ensued. At least 64 people were killed and about 350 wounded in the deadliest strike in the capital since 2001.

There was a certain symbolism to the fact that the target was an intelligence training ground for bodyguards protecting Afghan politicians and other dignitaries. Not even the people you trust to protect you are safe, seemed to be the insurgents’ message to their enemies. Most of the casualties were civilians, however. “The Taliban always say they kill the foreigners and security forces,” said Haroon Faqiri, who was 100 metres from the explosion. “But I saw hundreds of wounded civilians.”

Even for a city accustomed to explosions, this bomb was unusually powerful. Miles away, the pressure from the blast rattled windows and blew open wooden doors. Along the muddy river leading away from the blast site, metal storefronts were crumpled like cellophane. Afghans responded to the carnage with grief and solidarity, residents lining up outside hospitals to donate blood.

The announcement of the Taliban’s spring offensive is an annual occurrence. Warmer weather and new foliage for battle-cover herald months of intensified fighting. But this winter hardly saw a lull. Exploiting the vacuum left behind by the withdrawal of foreign soldiers, the Taliban made advances not only in their traditional southern and eastern heartlands, but also in the north.

Facing a leadership battle after it was made public last summer that the movement’s founder, Mullah Mohammed Omar, had died more than two years earlier, the Taliban are in need of military successes to unite their ranks. A demonstration of strength, such as the attack this week, might help doubting foot soldiers regain lost confidence.

The new commander of the American and NATO troops in Afghanistan, General John Nicholson, and the Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, saw it differently. The attack was a sign that “the insurgents are unable to meet Afghan forces on the battlefield and must resort to these terrorist attacks,” as General Nicholson put it—a sign, essentially, of Taliban weakness.

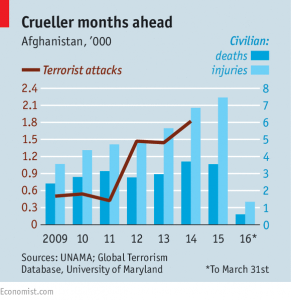

But the reality is that the Taliban currently control or contest more territory than at any point since 2001. Last year Afghan security forces, often fighting on multiple fronts, suffered record casualties: on average more than 1,000 soldiers or police were killed or injured each month. The deteriorating security situation is a major factor behind the exodus of Afghans. Last year Afghanistan was second only to Syria as a source of migrants to Europe. More than 200,000 Afghans made the journey.

Yet the Taliban are not on the verge of victory. Government security forces still control all the main towns and cities. Big advances by the Taliban have usually been reversed within a few days. Moreover, the Afghan army has learned to operate with fairly minimal help from NATO forces. Tactics have changed, with a retreat from exposed outposts in favour of deploying more forces that can be concentrated when and where needed. Those troops will also enjoy more close air support this year. Although the Afghan air force remains very much a work in progress, for this year’s “fighting season” it will be equipped with three new Mi-25 helicopter gunships and eight A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft specially designed for counter-insurgency operations. The chances of the American-led NATO assistance mission being boosted next year are also quite high. Under the current timeline, the American contingent is due to fall from 9,800 now to 5,500 by the end of the year. But the military advice Barack Obama has received is strongly opposed to the drawdown. If his successor is Hillary Clinton, she will not want to start her presidency with an Afghan security crisis. Her instincts are already more interventionist than Mr Obama’s; she may well wish to see a small increase in American troop numbers, accompanied by more concerted air support for the Afghan forces. Defeating the Taliban proved impossible; preventing them from winning is probably easier.