- The U.K.’s defeat at Jutland is a reminder of how a victorious force can get lazy

Foreign Policy Magazine

JAMES HOLMES

The popular imagination remembers World War I as a tale of trenches, mud, rats, and barbed wire. But the grinding ground war between the entrenched armies in France wasn’t the only conflict. In the east, Russia and the Central Powers fought a war of movement over vast plains. In the south, Italian and Austro-Hungarian troops froze in the white war of the mountains. On the periphery of Europe, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk frustrated the Allied thrust at Gallipoli, while far away German cruisers wreaked havoc along the South American coast.

If there was one thing shared in all these theaters, it was a leadership struggling to comprehend how quickly war had changed, and to reconcile the lessons they’d been taught with the grim realities of the ground. For most, it was a drawn-out education. But for the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy, which had assumed it would win the glory it saw as its birthright, it was a single sharp shock—one with lessons that the U.S. Navy should be heeding today.

The Great War’s maritime battle has much to teach a U.S. Navy that has faced no peer in battle since World War II, and not even the prospect of an enemy since the Soviet Navy’s demise in 1991. The U.S. Navy has fallen into some of the same vices that bedeviled the Royal Navy by the turn of the 20th century, and that were exposed at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

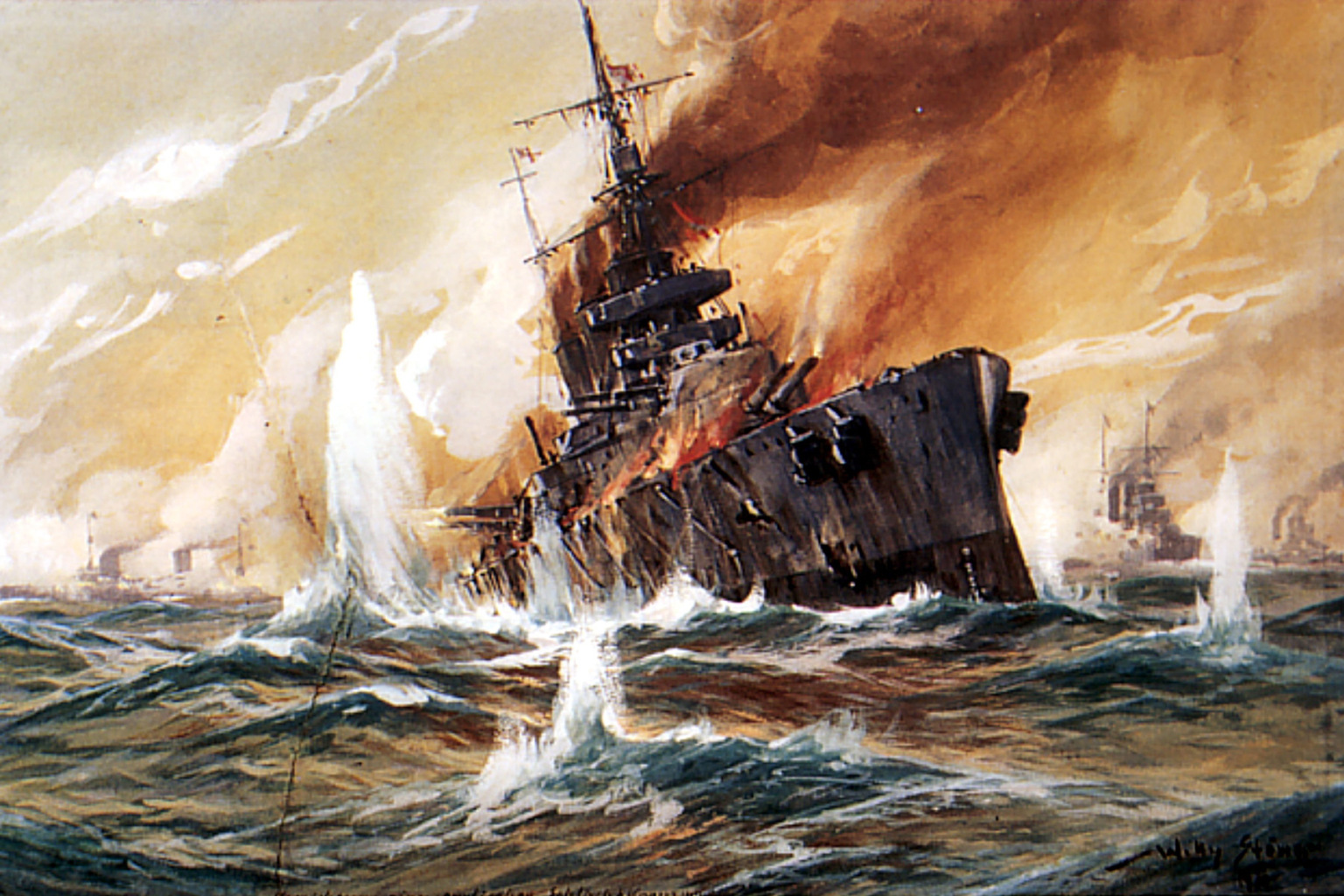

The Royal Navy had been anticipating a clash with the German Imperial Navy since the beginning of the war, in the confident knowledge that it would prevail. But at Jutland, off Denmark’s North Sea coast, the upstart German High Seas Fleet gave worse than it got against Britain’s Grand Fleet. The battle was inconclusive, but for an Admiralty that took British victory as the natural state of affairs, that was as bad as losing. Prewar British policy had been that the navy should be able to take on its two largest competitors at the same time. Yet so effective were German gunners, and so inept British maneuvering, that Battlecruiser Fleet commander Vice Adm. Sir David Beatty quipped: “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” That blood was quite literal; the British lost 14 ships and more than 6,000 men—double the price the Germans paid.

There was, indeed, something wrong with the bloody ships, but the Grand Fleet’s woes were more cultural than material. Ship design was one problem; handling was a worse one. Since the Napoleonic Wars a century beforehand, Royal Navy commanders had taken to scripting out fleet movements in minute detail. The Admiralty published signal books explaining how: The signals crew in a flagship would encode an order from the admiral in a complex series of signal flags, hoist the flags up the yardarm on ropes, wait for signal crews on other ships to read and decode the message, then execute the order by hauling down the flags.

This system sounds awfully intricate for saltwater surroundings, and so it was; its efficacy was dubious even during peacetime maneuvers. Fleets mainly consisted of steam-powered surface ships whose boilers burned coal or thick oil. They belched forth black smoke, sometimes deliberately made by skippers to obscure their movements. Inadvertent smoke, hazy skies, or winds that twisted flags could blind the fleet just as easily, disrupting the nautical choreography that gladdened admirals’ hearts.

The sea is unfriendly to parade-ground efficiency by its nature. Few formations survive first contact with the enemy. They scatter amid the clangor of arms. Fighting degenerates into melees that pit individual ships or flotillas against each other. The battle’s outcome is the sum of many small-scale engagements. Tactical choreography hurts the cause if ship or fleet commanders are unused to operating off-script—and off-script is where single-ship encounters take place. Individual enterprise and derring-do, not orders from central authority, decide between triumph and defeat.

None of this should have come as news to British tars, but by 1916 the Royal Navy had in effect forgotten about the rigors of war against a peer competitor. Combat is the arbiter of what does and doesn’t work in naval affairs. But 19th-century Britain had no maritime rival to provide a reality check. Conflicts were limited to gunboat diplomacy, hunting slavers, and bombarding weak states. Fresh complexity encrusted each edition of the Signal Book as the nineteenth century went on, but few noticed that the system was unfit for a combat setting.

Tranquil times let Royal Navy officers indulge their proclivity for authoritarian command. Control freaks gravitate to the naval officer corps. What do officers do if there’s no one to fight? They obsess over scripted ship movements, strict obedience to orders, administrative busywork, spit and polish, and sundry other matters that do little to hone battle efficiency. One of Murphy’s Laws of Combat holds that no combat-ready unit has ever passed a peacetime inspection. But if the leadership talks itself into believing combat will never happen, a navy spends its time preparing for peacetime inspections.

At Jutland, history issued a grim verdict on British administrative prowess. Germany had only started building an oceangoing battle fleet around the turn of the century. Consumed with administrative trivia, the vaunted British Navy—which had ruled the waves for a century since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805—came off worst against a fledgling navy crewed by landsmen reared on continental combat.