Riaz Ahmed Malik

Group Editor Daily National Herald Tribune and Daily Al-akhbar

Magok-i-Attari Mosque

The Magok-i-Attari Mosque is located immediately west of the Lyabi-Hauz pond and architectural ensemble. It is one of the few structures in Bukhara that was partly (or wholly) built prior to the Mongol invasions of 1219-21. According to Edgar Knoblauch it is the oldest surviving mosque in Central Asia, built atop the foundations of a temple that was already present in Sogdian times.

The historian al-Narshahki, who completed his History or Bukhara in 943 or 944, notes that the mosque was built on the site of a fire temple that pre-dated the arrival of Islam; most likely this was a Zoroastrian fire temple used by the Sogdian population of pre-Islamic Bukhara. Narshahki also mentions that a thriving fair was located nearby that traded in idols twice a year with 50,000 dihrams changing hands in a single day. Most unusually, the fair was tolerated by the Islamic rulers and continued to exist even in Narshahki’s own era, indicating that a substantial part of the population had yet to convert to Islam.

Narshahki refers to the mosque as the “grand Mosque of Makh” which took its name from the bazaar of Makh where the trade in idols flourished (the bazaar, in turn, took its name from a legendary Bukharan king named Makh). However, later in his chronicle Narshahki refers to the building as the “mosque of Maghak” which is the same as its modern name Magok meaning “recessed”; this suggests that the mosque was already located below ground level even in his own time. Today, the mosque is located some 4 meters below the level of the surrounding city as many centuries of building and rebuilding have raised the overall ground level in the surrounding district. The remainder of the mosque’s name, attari, means “perfumers” in reference to the fragrances also traded at the bazaar.

No traces of the Mosque of Makh remain except for bits of alabaster decoration and traces of brickwork found during archaeological excavations. Presumably the structure was either destroyed or burned down, though the present layout probably follows its floorplan. The current structure is a palimpsest of various architectural ages beginning with the 12th century; the mosque’s southern portal was probably constructed by the prolific builder Abd al-Aziz II, a Kharakhanid-era ruler who also built the Namazgah Mosque and Minaret of Vobkent, both of which survive. The portal is laid out with two sets of paired quarter-columns on opposite sides of the pishtaq. The quarter-columns are turned back to back, giving each set the appearance of half-open books or two scrolls standing side-by-side. The historians Bloom and Blair suggest this arrangement has roots in pre-Islamic design. The central portion of the pishtaq is quite similar in design to that of the Chashma-Ayub of Vobkent. The pishtaq’s arch is crowned by an epigraphic frieze, now partially destroyed, in blue glazed tiles.

The interior of the mosque is laid out in a 3 x 4 bay grid pattern with domes over each of the bays. Two of the central domes are raised on high drums to admit light.

Further alterations to the mosque were made from 1547-48 by the Shaybanid rulers of Bukhara who added a monumental east-facing pishtaq. The surrounding streets were already much higher than the ground level of the mosque; the contradiction was awkwardly resolved with a set of stairs that lead down into the interior from the pishtaq’s antechamber.

In modern times the mosque has been converted into a museum of carpets. Access to the interior of the building is permitted but visitors must pay an entrance fee.

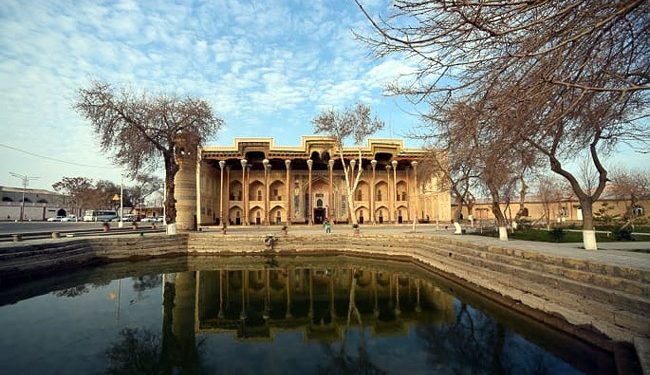

Bolo Hauz Mosque

of Bukhara

Located on the western edge of the former registan, or plaza, the Bolo Hauz stands opposite the Ark Fortress in a kosh arrangement with the registan between them. Its name means “above the pool”, referring to the octagonal hauz, or artificial pond, located directly in front of it (mosques in Bukhara traditionally incorporated a hauz, whenever possible; see also the Hoja Zayniddin mosque). Begun in 1712, early in the reign of Abu’l-Faiz Khan (r. 1711-47), it is one of the last and finest of Bukhara’s major buildings prior to the modern era.

The Bolo Hauz is a Friday mosque, large enough to host the special noon jumah prayers for a large percentage of the population. In practice, the mosque served as the personal house of worship for the ruling Khan, who often traveled to and from his Ark palace with great pomp and ceremony, cushioned by a continuous spread of carpets laid specially for the occasion. It was here that his name was read aloud in Friday prayers, underscoring the Khan’s absolute authority over the city and all its affairs.

The mosque is a curious hybrid design reflecting Bukhara’s harsh climate-stifling heat in summer months, bone-chilling cold in the winter, with periods of pleasant weather in between. As in Khiva, architects adapted to these extremes by designing buildings with north or east facing iwans which were open on one more sides, providing ample ventilation and shade in summertime. In winter months, a building’s occupants retreated indoors where fires might be lit. At the Bolo Hauz, the core of the building is its winter mosque with heavy brick walls, capped by a spacious dome. The interior is decorated with muqarnas-style vaulting, particularly in the antechamber adjacent to the mihrab. In the summer, worshippers would have used the expansive iwan on the east side of the building comprising a 20-pillared hall measuring 42 x 10 meters, bounded on three sides by mosque’s brick walls. As Chuvin and DeGeorge note, this design recalls the “forty pillars” (Chehel Sotoun) common in Persian architecture. Each of the pillars is fashioned from two tree trunks connected end-to-end (to extend the length) and is made of walnut, elm, and poplar wood.

It is, however, important to note that construction of the 20-pillar iwan hall was a relatively late development, occurring at the beginning of the 20th century. Prior to that period the mosque comprised either only the central brick core or an earlier wooden iwan which no longer survives. In any case, it is fortunate that the iwan escaped destruction in the 1920 siege of Bukhara by the Red Army which resulted in the loss of most of the adjacent Ark Fortress which was ravaged by fire.